While only making up 3.8% of the Australian population, First Nations peoples manage over 50% of Australia’s national reserve system - a total area larger than Chile - and the government has plans to grow this estate further.

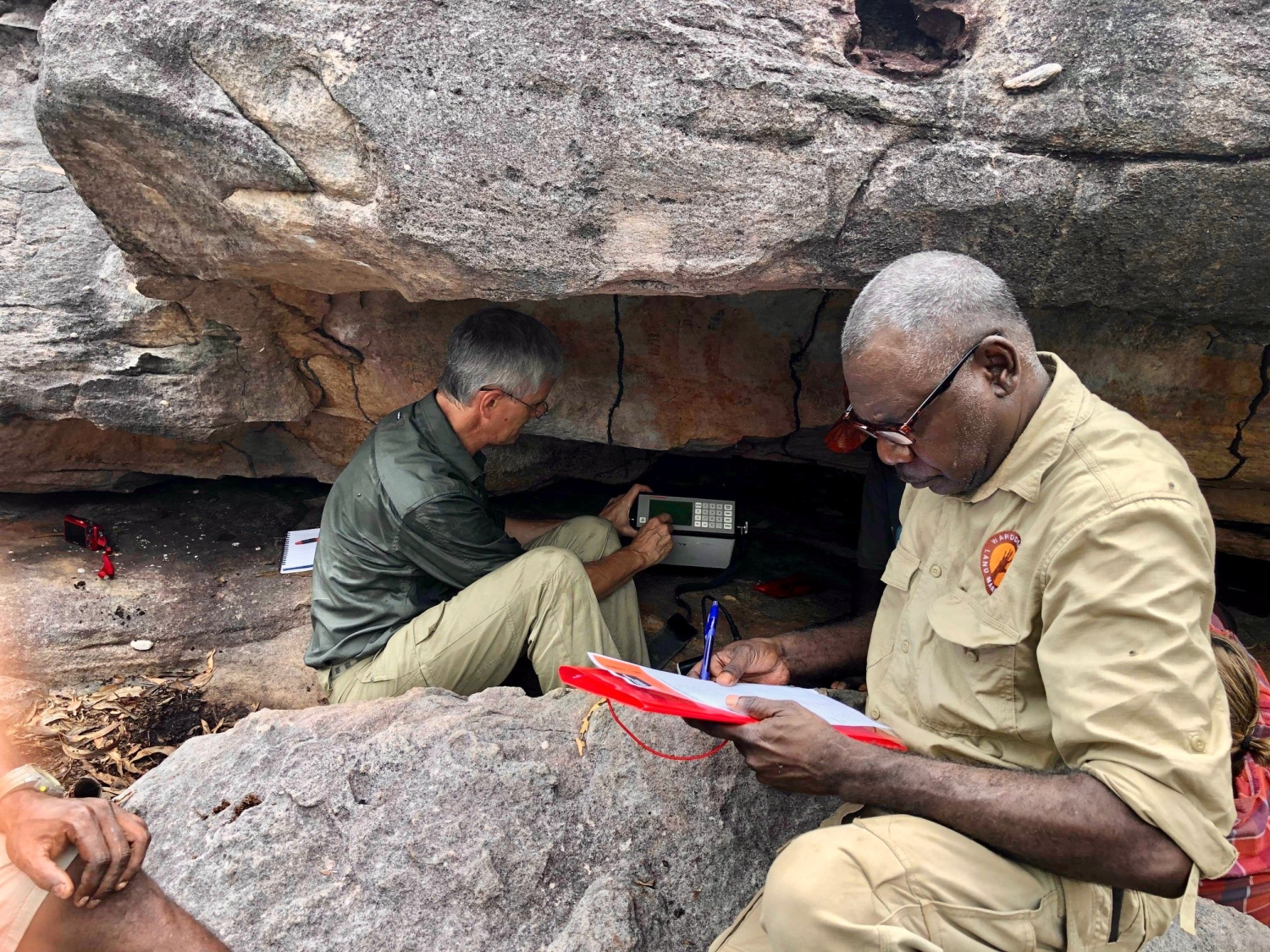

These landscapes are actively managed by Indigenous rangers, often operating out of isolated homeland communities across Australia. In these places, First Nations people have been caring for Country for tens of thousands of years: practicing their culture, protecting native animals, burning to prevent wildfires, monitoring the health of waterways and reaping the rewards of sustainable harvesting for food and medicines.

Locally, nationally and globally, this Indigenous-led conservation creates immense value in terms of reducing carbon emissions, restoring and maintaining natural capital and improving social development. Every $1 invested creates up to $3.40 in social return including better economic, health and educational outcomes.

Across an estimated 1,100 remote and very remote First Nations communities in Australia, these communities are going backwards on many indicators of disadvantage and inequality. People here rarely experience change alongside national improvements, and they sit in stark contrast to the same indicators for remote and very remote non-Indigenous communities. One example is the 14-year gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people living in remote and very remote areas.

Across the Northern Territory in particular, outcomes for First Nations peoples have generally worsened or stagnated across all target areas of Closing the Gap, from an already-low starting point. They are vastly unsupported, underfunded, and underrepresented.

In the remote communities where KKT works, people express a deep desire for appropriate education and jobs but they often don’t even have reliable clean water and energy, housing, accessible roads or mobile coverage. They experience living conditions that would not be tolerated in mainstream Australia.

What we hear is that people want to live on their homelands, live together as families, and enjoy the same opportunities as the rest of Australia.

This is a fact recognised by all sides of politics: when First Nations peoples have representation and input in the matters affecting them, the outcomes are better. KKT has seen this in action.

The Kabulwarnamyo community asked for their own independent school, and now consistently achieves over 95% attendance rates across three locations.

Traditional Owners in Arnhem Land established a world-leading fire management program, and now consult and collaborate every year to abate around 600,000 tonnes of CO2e.

Nawarddeken daluk (women) asked for dedicated support and resources to enter and engage in ranger work, which resulted in a doubling of workforce participation in one year.

Members of Mimal Land Management sought independence from the regional statutory authority in 2017, and the organisation has since grown from delivering seven projects to over 80 active projects.

But, ultimately, KKT shouldn’t have to exist to fund all the gaps; to cover basic needs such as food security, services, infrastructure and teaching salaries.

Most Bininj (Aboriginal people of West and Central Arnhem Land) who we speak with are reckoning with a deep mistrust of government and a lack of faith in political processes. This is to be expected after decades of damaging and dysfunctional policies. We have heard from people who no longer vote because they never see improvements.

These conversations often return to the importance of securing a mechanism for representation that will weather changes in political parties and representatives; that will rise above the deeper failures of our political system. The Voice has potential to achieve this, if it is designed well.

"I hope things will change if we’re all in the one family and on the right track” - Dean Yibarbuk, Traditional Owner of Djinkarr and Co-Chair, Karrkad Kanjdji Trust

“It’s Warddeken [Land Management Ltd] and Mimal [Rangers Aboriginal Corporation] and KKT and others like that out here fixing everything” - Fred Hunter, Bolmo Deidjrungi clan member and Director, Karrkad Kanjdji Trust

“It’s important for our kids, our future, that we take a chance at change. But it’s very hard to hope” - Cindy Jinmarabynana, Traditional Owner of Ji-bena and Director, Karrkad Kanjdji Trust

There are around 150,000 First Nations men, women and children who live across 86% of the continent in remote and very remote areas. They deserve better.

If we believe First Nations peoples should be supported to continue their contributions to global environmental and social goals, to continue caring for this unique land and protecting its immense ecological value, then we must find a way to listen better. We must support communities working to create a better future, and give them a say in that future.

Bininj have many hopes, many dreams and many fears. The Voice may not be the complete solution, but we know how much can be achieved by simply creating the space to listen. This is the rare opportunity for change in front of us today: to embed a space for listening in our systems of government which can, in turn, improve the response and thus the outcomes.

For these reasons, we encourage Australians to vote Yes, and we look forward to the post-vote consultations which will help to design the best possible representative body and continue to improve it over time.